A unified theory of moronic hype cycles

In early 2015 I was in San Francisco getting ready to be interviewed by Emily Chang on Bloomberg. My team and I arrived 45 minutes before going live, and I asked the account manager at our PR agency what the likely top three questions would be. She said, “The first thing Emily will ask is, ‘What’s Nexon’s VR strategy?’” I replied “That’s easy, we have none, VR sucks.”

They looked at me in horror, and for a brief moment were uncharacteristically speechless. She then said “You can’t say that! Everyone knows VR is the next big thing in games!” Our prep meeting devolved into an argument, in which I tried to convince the team very few people use a VR device regularly or even want to, and that even if all the user experience issues were immediately fixed VR likely wouldn’t matter much for games for at least a decade. In her defense: everyone was talking about VR. VR had just been on the cover of Wired, and Facebook had just acquired Oculus. You could be forgiven for thinking VR was the future.

Emily did indeed ask me what our VR strategy was, and to my regret I did not reply “It sucks, we have no strategy.” I answered with an anodyne statement of how it’s really interesting tech, it increases immersion, and we are looking into it. I doubt many viewers thought my answer was interesting. Ten years on VR is still a tiny market, and generates no meaningful share of the $200 bil games industry.

Derek Zoolander was the male model character from Ben Stiller’s film — glamorous, obsessed with new trends, and completely empty-headed. I use him here as an avatar for the type of thinking that shuts off people's brains, making a trendy topic look brilliant at first glance, but collapsing the second you ask for substance.

Over the decade that I ran Nexon, our industry experienced a relentless procession of hype cycles, including esports, Cloud/Streamed gaming, NFTs in games, and The Metaverse. Each was considered to be either the Deus Ex Machina that would drive a new wave of growth or the angel of death that would disrupt the incumbents. Like every other game CEO, I fielded literally hundreds of questions every year from press and investors.

It is easy to look back and ridicule everyone involved. But the phenomenon of game industry hype cycles is actually serious business. The fallout from these mass delusions has been tens of billions of capital destroyed and thousands – possibly tens of thousands – of careers upended. The degree of destruction leaves an important lesson: a vital skill is to identify and understand hype cycles, and to filter and orient yourself when they inevitably arise.

But it’s very difficult to discern what matters and what doesn’t matter in the moment. We need an analytical framework.

The good news is hype cycles in our industry seem to follow a pattern.

Many players feed a hype cycle, but the sellers are the loudest. Companies pitch their vision, VCs promote their portfolio companies, reporters chase clicks, and consultants write reports to sell their services. Together they form a highly persuasive chorus.

A great example was Bobby Kotick pitching esports franchises to traditional sports owners. He needed revenue; they needed growth. Team owners saw their kids gaming and assumed, “In the future, kids will fill esports arenas the way we filled football stadiums.” Both sides had every incentive to believe the hype, although only the seller made money.

Most hype cycles don’t begin as bandwagoning. Smart people had a thesis they believed in. Esports was about open-access, monetizable competition. VR promised immersion and new experiences. Streaming games held out the promise of ubiquity. The Metaverse promised a new way to interact with the internet.

In investing, this matters. Refusing to participate in hype can mean missing great returns. As Bill Gurley has pointed out, in the 1998–2000 internet bubble a massive percentage of returns came in the final 100 days before the bubble burst. Aversion to hype means you can miss out on venture returns.

Mitch Lasky has spoken publicly about passing on Oculus. He was right that its chances of surviving as a stand-alone company were close to zero. But hype created a non-rational outcome when Facebook paid over $2 billion, and by being “wrong for the right reason,” he missed hundreds of millions in returns.

For gaming executives, the risk of missing is just as serious: platform shifts create the biggest winners, which makes chasing chimeras feel rational. One might be real. Many lasting franchises began as “killer apps” for new platforms: Mario on the NES, Madden on the Sega Genesis, Halo on the Xbox, FarmVille on social networks, Clash of Clans on mobile.

The point isn’t that hype made these good businesses; it didn’t. It’s that hype cycles always start from a rationale that smart people can believe, and that makes them dangerous for those who need to worry about the long term.

It is very hard to resist a hype cycle. Human survival has always depended on groups, not individuals, so evolution wired us to care deeply about what others think. There are two layers. We care about status because throughout evolution it determined survival. And we absorb tribal knowledge because the world is too complex to decode alone. Conformity once kept us alive; breaking from it still feels dangerous.

But the very instincts that kept our ancestors from being eaten by lions thousands of years ago are the ones that today push us into bubbles. Successful investing requires going against our tribe, to be early to an idea, and to be right.

The struggle to think independently has deep intellectual roots. Benjamin Graham emphasized that value investing was largely about temperament – it requires fighting the pull to conform. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky showed how humans behave like emotional, shortcut-driven creatures, driving social pressures that fuel bubbles. French philosopher René Girard went further: desire is mimetic. What feels like independence is usually imitation. We want what others want.

So a vital skill for anyone investing time or money in a hype-laden industry like videogames is to separate empty fads from valuable innovation, and to do that you need a tool to make smart decisions. The best way I have found is to focus at all stages on the user experience. If the UE sucks, you don’t have a product anyone wants, and therefore no business.

To help you get specific, here’s a simple 3-question Fad Audit:

To see if these questions are useful, let’s apply them to the biggest fads of the last decade.

Esports became a hot topic in the US around 2015 but had been bubbling in Korea for at least 10-15 years prior. From afar the appeal was strong: a new generation of fans preferred esports arenas to football games, and Twitch streams to televised sports. The experience of watching esports mimicked a traditional sport, with fans cheering, and skilled talking heads commenting on the game.

Was viewing esports tangible? Yes. You could watch a game on Twitch or go to an event. But was it a great user experience? This is where it fell apart. Outside of a few marquee events like Blizzcon, live audiences were thin, and the experience was rarely better than watching a skilled streamer from home. From a distance esports looked huge, but up close the numbers did not hold. The hype far exceeded reality.

The deeper problem was that esports mainly appealed to people who already played the game. Non-players had little interest, unlike traditional sports where fans enjoy the game without playing themselves. And for players, the staging to make esports look like a traditional sport often got in the way of what they actually wanted: to study how skilled players won. And, as Matthew Ball has pointed out, professional sports are designed to be watched. The rules, pacing, and presentation all serve the spectator. Video games are the opposite: they are built to be played, with systems that reward control and mastery, not observation.

Meantime, advertisers were the other customers of a sponsor-supported experience. What was their user experience? Early esports attracted significant sponsorship dollars. But as detailed in this excellent piece from 2019, the payback for sponsors was unclear at best, driven by low engagement stemming from the user experience problems above. The test sponsorships dried up, and with the illusion of a mass audience gone, the business model collapsed.

For sheer ability to ignite a hype cycle, the 2013-2016 rise of VR was hard to beat.

On the surface VR seemed to bring the cyberpunk vision of William Gibson and Neil Stephenson to life. The leader at the time – Oculus VR – had a dynamic founder-evangelist, and was then bought by Facebook for $2+ billion. And most of all, Oculus was an incredibly compelling demo. So it was very tangible (you could try it out yourself), it felt completely new, and it promised a revolutionary experience: an input-output mechanism that seemed much more immersive than the old screen and keyboard/mouse/controller. It was hard to walk away from the (usually brief) demo not thinking you had seen a real sci-fi future.

But that “much better” user experience was highly deceptive. While on the surface VR seems more immersive, in many ways it was the opposite of immersive. Whether it’s tennis, chess, Monopoly, or StarCraft, gamers become immersed in a game largely from the experience of being challenged to make decisions or take actions within a set of rules.

Immersion comes from rapidly gathering information, making decisions, and immediately translating them into control movements. A user interface has to enable that process, not get in the way. Counter-intuitively, VR got in the way. Yes you could move your head around in a way that felt very realistic (walking on a virtual i-beam 30 stories up in a construction simulator quickly induces vertigo). But in almost all cases a simple screen, keyboard and mouse is actually a lot easier for playing in a 3D environment, and therefore more immersive. And VR struggled to deliver the high-speed pixel accuracy that made sports and shooter games so difficult to master. These are the types of UE subtleties that are largely lost on non-gamers, so many investors and analysts were utterly fooled by VR. VR looked like the future, until you tried living in it.

Streaming Games

The promise of streaming games is to play console games without a console. The game is hosted remotely in the Cloud (actually, on a GPU-equipped server near the player to reduce latency) and streamed over high-speed connection. The concept was first delivered by OnLive around 2008 and then Gaikai a couple years later. After those two efforts largely failed and then were sold, Google dusted off the concept and launched Stadia in 2019. Google’s unique take was that their existing CapEx in server farms would make the unit economics work where it didn’t for OnLive and Gaikai.

The product was certainly tangible. Despite early skepticism that it would work, OnLive, Gaikai and Stadia each delivered relatively reliable cloud-based services as promised.

Did it enable something new? Not really. You still played console games on a screen with a controller. The only novelty was avoiding the upfront cost of a console in exchange for a smaller startup fee and a subscription. But console gamers never saw hardware as a barrier, and many even preferred owning the box. Lowering the cost did not expand the market, since console gamers are already hardcore.

Another supposed perk was to instantly flip between a large library of games. But immersive games of the type played on consoles aren’t Netflix. Players spend 40, 100, even 1,000 hours in a single title. Channel surfing isn’t in the nature of the medium.

And without anything truly new in the user experience other than the billing mechanism, was the user experience much better? Not at all. With so little content it was way worse. And for the game publishers (the other customer in a 2-sided platform) it was also worse…not enough consumers. Despite intense media coverage in 2019, Stadia, like OnLive and Gaikai before it, died a quiet death in 2022.

On paper, blockchains and online games looked destined for each other. Since the early 2000s online game companies had been selling virtual goods, and player-to-player trading had existed almost as long.

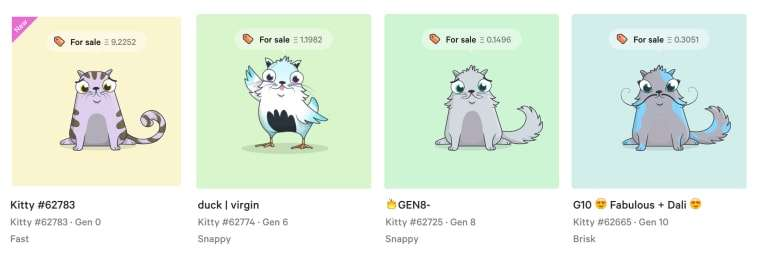

In 2017 and 2018 games like CryptoKitties and Axie Infinity burst onto the scene and generated massive excitement. Breeding virtual creatures looked like a new form of play, early revenues spiked, and the Ethereum network strained under the volume of on-chain transactions. Other projects like Decentraland and Embersword pushed further, building 3D worlds where users could buy land and items long before the worlds were finished.

Early NFT games promised several novel benefits. Players could own items outside the control of the game company, and those items might rise in value. This was not a crazy idea. Grey markets had existed since the early days of online games, and many players made money farming and trading. NFTs promised to formalize that.

But the user experience problems were immediate. Wallets and transactions were cumbersome, which raised customer acquisition costs and limited reach. More fundamentally, paying for leveled-up items or characters stripped away the challenge, and challenge is what makes a game a game. Put simply, they took the game out of the game.

What remained was a status-driven economy, where farmers leveled up assets cheaply to sell to status seekers. That market collapsed once the status seekers left the hall of mirrors. This is why experienced MMO operators like Nexon, Blizzard, Tencent, and NCSoft spend enormous time and money fighting bots and gold farmers: they know such activity undermines the game itself. As for the speculators, they got wiped out. Tokens like Axie Infinity’s SLP fell more than 99 percent from their peaks, and Decentraland’s currency dropped over 94 percent.

Net, the NFT game companies forgot that a game was still necessary to make an NFT game. Owning items outside a company’s control sounded appealing, and speculation created a brief and intense sense of momentum, but those factors did not matter without a game at its core. As obvious as it sounds, taking the entertainment out of an entertainment product spells collapse.

The Metaverse was the mother of all hype cycles, a black hole that consumed the games industry and indeed the broader tech industry between 2022 and 2024.

It promised a fully simulated alternate life, blending ideas from VR, NFTs, and online worlds, wrapped in cyberpunk tropes from Neuromancer, Snow Crash, Ready Player One, and Black Mirror.

The hype cycle ramped up considerably when Facebook changed its name to Meta in 2021. Equity analysts adopted the Metaverse nomenclature. McKinsey later piled in, projecting that the Metaverse “market” would reach $5 trillion by 2030. Accenture projected $1 trillion of Metaverse revenues by 2025, and like other management consultancies offered to help companies from any industry develop a Metaverse strategy.

Among all this hype, thoughtful and experienced participants such as Matthew Ball and Tim Sweeney stood out. Sweeney had been positioning Epic around this vision since 2016, long before it became a buzzword, and Ball later expanded the idea in his comprehensive book The Metaverse. Both took the time to at least posit a rational definition: “A massively scaled and interoperable network of real-time rendered 3D virtual worlds that can be experienced synchronously and persistently … with continuity of data, such as identity, history, entitlements, objects, communications, and payments.” And they took pains to detail the technical and other challenges to bring that vision to reality.

How did The Metaverse land in our Fad Audit? It failed all three, badly.

Was it tangible? Not at all. As mentioned, despite Ball’s and Sweeney’s influence, there was almost no clear definition or consensus on what a Metaverse is. In the absence of a definition, everything was a Metaverse and everyone was claiming to be one: from glorified MMO’s to vaguely defined education applications.

Did it enable something new? In concept yes, but since it promised everything, in practice no. Roblox had been in existence for a decade as a two-sided platform of game makers and consumers, before it rebranded itself as a Metaverse in 2021. Decentraland positioned itself as a metaverse but plays a lot like a low-tech version of Second Life (a virtual world from 2006) with NFTs added.

Did it improve the UE? Again, yes in concept but in practice no. To most people reading about The Metaverse, the UE would be akin to Ready Player One. But none of the practical problems were figured out. The most high profile offender of this disconnect between vague vision and practical implementation was Meta’s Horizon Worlds. Its launch was widely ridiculed, and despite the massive investment in world development and underlying tech, couldn’t even garner interest from its own developers and testers, who had to be cajoled into using it.

Look closely at the user experience and the problems appear immediately. The key question is about in-world economy and interoperability. Anyone who has built an MMO understands a fundamental problem is managing inflation. Connect those worlds into a larger ecosystem and the problem rises exponentially. Inflation earned in one world carries into another, much like rich countries exporting inflation to developing countries in the real world. And how is a sword in one world supposed to operate in another world? Games and their tools are tightly balanced, down to single percentages of damage or range or value. Simply throwing them together destroys a game’s fun. And no consumer stays in a world that’s not fun.

Then there’s the problem of simulating reality. Even at near-photorealistic levels, the graphics layer is only the veneer. Do items in that world behave realistically? How do you simulate weather? Does rain pool into rivers and lakes? Do buildings have structural integrity? If one denizen breaks a wall for fun, is it ruined for everyone else?

And perhaps most fundamental: Why do I want to be here? Chatting and building things in a simulated 3D world are not compelling by themselves. People must have a reason to go to a place, real or virtual. The hype never grappled with these basic user experience questions.

In the end, the Metaverse didn’t fail because it was too early; it failed because it never solved a problem worth solving. It reflected our fantasies instead of fulfilling them.

Mocking fashion trends and the people who participate in them after the fact is fun, but it’s also valuable. These weren’t harmless fads. The malinvestments destroyed billions of dollars of capital that belonged to pension funds, retirement accounts, and ordinary savers. For those making capital investments, ignoring user experience questions isn’t just naïve, it’s a breach of fiduciary duty.

They also wasted something more precious than money: the time and attention of talented developers and technologists. A decade spent chasing fads could have been spent building things people actually want.

The rigor required to analyze hype cycles isn’t primarily financial, it’s about products and user experience. Why would a customer care? Why would they pay, show up, or change behavior? User Experience is the most valuable filter.

Companies that do this well look spiky from the outside. Their product focus leads them to areas where they can articulate a compelling user experience and ignore those areas where they cannot. Nintendo and Games Workshop are two great examples of companies that habitually go against the mob because they focus on the customer experience. Both weathered enormous criticism for not jumping on the fashionable trends of the day. Both experimented with new technologies, but in a customer-focused way, and are now two of the healthiest companies in entertainment. Contrast them to Square and Ubisoft, who jumped on nearly every hype cycle, burning through cash while their core businesses rotted.

The solution isn’t cynicism. Rigor allows companies to lean in when it matters and filter out noise when it doesn’t. The test is simple: if a company can’t explain, in plain terms, how their product makes the user experience 2x better, it isn’t a business. It’s a fad. And you should run.

Discerning the real from the hollow is more important than ever, at the start of the largest hype cycle – and world-changing technological revolution – of our lifetimes. That’s the challenge of this moment, and the subject of a future essay.