If you have a strong opinion about the future of AI in games, you are probably wrong

In the mid-1990s, I joined one of the hottest startups in Silicon Valley: PointCast. It promised to deliver the internet to you, without all the bother of actually browsing it. Everyone thought it was the next big thing.

The hype was immense. PointCast turned down a $450 million buyout offer from News Corp – a huge number for the time – before earning any meaningful revenue. Within three years the company was gone.

Watching our rocketship disintegrate was humbling. But the real lesson, the one that has compounded every year since, was about predicting the future during times of technological upheaval. There were many persuasive opinions about how the internet would unfold by the biggest media titans of the day. Yet nobody foresaw what actually happened: sites like Craigslist, YouTube, X, Wikipedia, Facebook, and Instagram wiped out most of traditional media and entertainment, and then Netflix, Spotify, and Amazon finished the job.

I’ve seen the same pattern many times since then. When something truly new appears, we frame it through the metaphors of what came before. AI seems no different.

We imagine the future as a slightly upgraded version of the present. History is full of people blindsided by new technology.

In 1914, an adult raised in the intellectual world of the Victorian age could not imagine the horrors that lay ahead. They entered World War I with cavalry charges and found themselves fighting with machine guns, airplanes, tanks, and poison gas.

Faced with rapid change, we reach for the familiar. Every generation fights the last war. The media titans of the 1990s treated the internet as digital paper, “500 channels” and “The Information Superhighway.” These were clumsy metaphors that implied faster versions of what they already knew, which was linear media. The idea of hypertext, the ability to jump across ideas instead of moving in a straight line, didn’t fit their mental model.

In Derek Zoolander, Videogame Exec, I detailed the industry's tendency to get trapped in fashion cycles: VR, blockchain, the metaverse. Each promised a deus ex machina for the industry but delivered little.

AI has the same hype signatures as the previous hype cycles I listed, so it deserves the same scrutiny.

Is it tangible? Yes. AI is already embedded in the tools we use every day, from writing assistants to image generation to code completion. Millions of people have integrated it into their work and daily routines.

Is it new? Yes. The last wave of “AI” in consumer products — voice assistants like Siri — was narrow and brittle. Systems like ChatGPT and Grok are qualitatively different, capable of reasoning and creation. Art, music, and code generation at this level simply did not exist before.

Is the experience meaningfully better? Yes. For many people, it has become indispensable almost overnight. A simple test: take GPT or Grok away from someone who has used it regularly. The gap it leaves is immediate and obvious.

By those measures, AI passes the fad audit with ease. It carries the empty hype signature of a bubble but the real-world utility of a foundational shift.

We live in a time of massive change, so it’s useful to orient ourselves in the history of human communication. The best framework I’ve seen for this comes from Ben Thompson in two separate Stratechery essays, here and here. (These two pieces are behind a paywall, but Stratechery is worth every penny.)

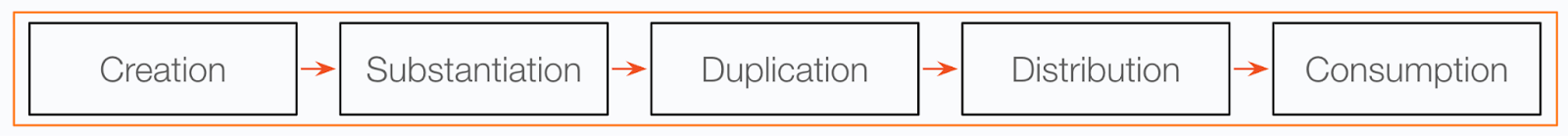

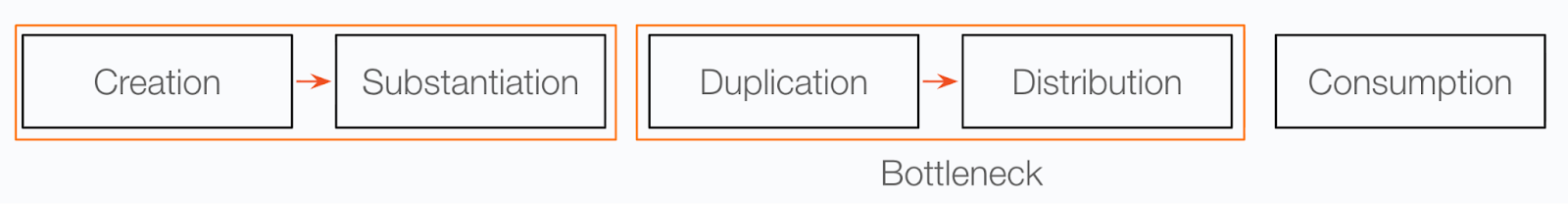

Thompson describes the history of communication as a series of unbundlings, where each new medium removes a bottleneck in the flow of ideas.

For hundreds of thousands of years, the sole form of communication was one human speaking directly to another: creating an idea, putting it into words, delivering it through speech, duplicating it by repetition, and distributing it one-to-one or to a small group in person.

Writing unbundled speech from presence, allowing ideas to reach across time and space. It required literacy and manual transcription, so spreading big ideas meant employing armies of scribes and monks to copy texts by hand.

The printing press unbundled creation from duplication. Gutenberg’s invention replaced labor with capital, as one press could reproduce what once took a monastery. Leverage shifted to those who owned presses and could distribute at scale.

The internet unbundled duplication from distribution. Ideas could now move globally at near-zero cost, removing the physical bottlenecks that had sustained publishers and broadcasters for centuries.

AI is now unbundling the creation of an idea from its substantiation, the act of turning that idea into usable form. It is removing the final bottleneck between thought and expression: writing the words, painting the image, filming the scene, or coding the system. When you ask Midjourney to illustrate an idea or ChatGPT to draft a letter, you are already offloading the substantiation of that idea. You are forming the thought but letting AI give it form.

Thompson was describing linear media, content that is consumed once and fades in value. But games are interactive systems and communities built on shared rules. The substantiation of such systems will look different from linear media, but the pattern is the same. Every unbundling changes who the winners and losers are, and AI is about to do the same for games.

Using Thompson’s framework, we can think about AI in games through the lens of substantiation or realization, the process of how ideas become real. The pace of change makes forecasts futile, but the tools that are already changing how we work are right in front of us.

The first layer is about the tools that help humans build better games, where most of the visible action in the industry is happening today.

Visual Realization: Tools like Midjourney and Sora are now standard for prototyping visual ideas. They’re still too coarse for final production, but better control will change that quickly. Traditional motion capture is costly and slows iteration, so Embark Studios built an AI-driven locomotion system trained inside a procedural physics simulation. In ARC Raiders, characters learn to walk, run, and fight through trial and error, much like an infant learning balance. It hasn’t replaced mocap for human characters yet, but it already powers their evil death robots.

Programmable Layer: Voice, dialogue, and code are converging into a single software layer. What once required separate disciplines — writers producing thousands of lines of text, actors recording them in studios, coders integrating the results — is starting to operate as one programmable system.

Tools like Eleven Labs enable small teams to create voice performances without access to professional actors or studios. As control improves, more developers will adopt the technology. Writing NPC dialogue is expensive, tedious, and rarely the most compelling part of a game, but models trained on richer material can make interactions more meaningful and emotional. As Steve Jobs imagined over 40 years ago, we’re inching toward tools that enable us to “capture the worldview of an Aristotle” by talking to him. Fully agentic coding remains out of reach, but code completion tools already accelerate development, improve reliability, and help modernize older codebases. Each of these tools turns a formerly manual creative process into programmable work: editable, testable, and responsive to real-time creative iteration.

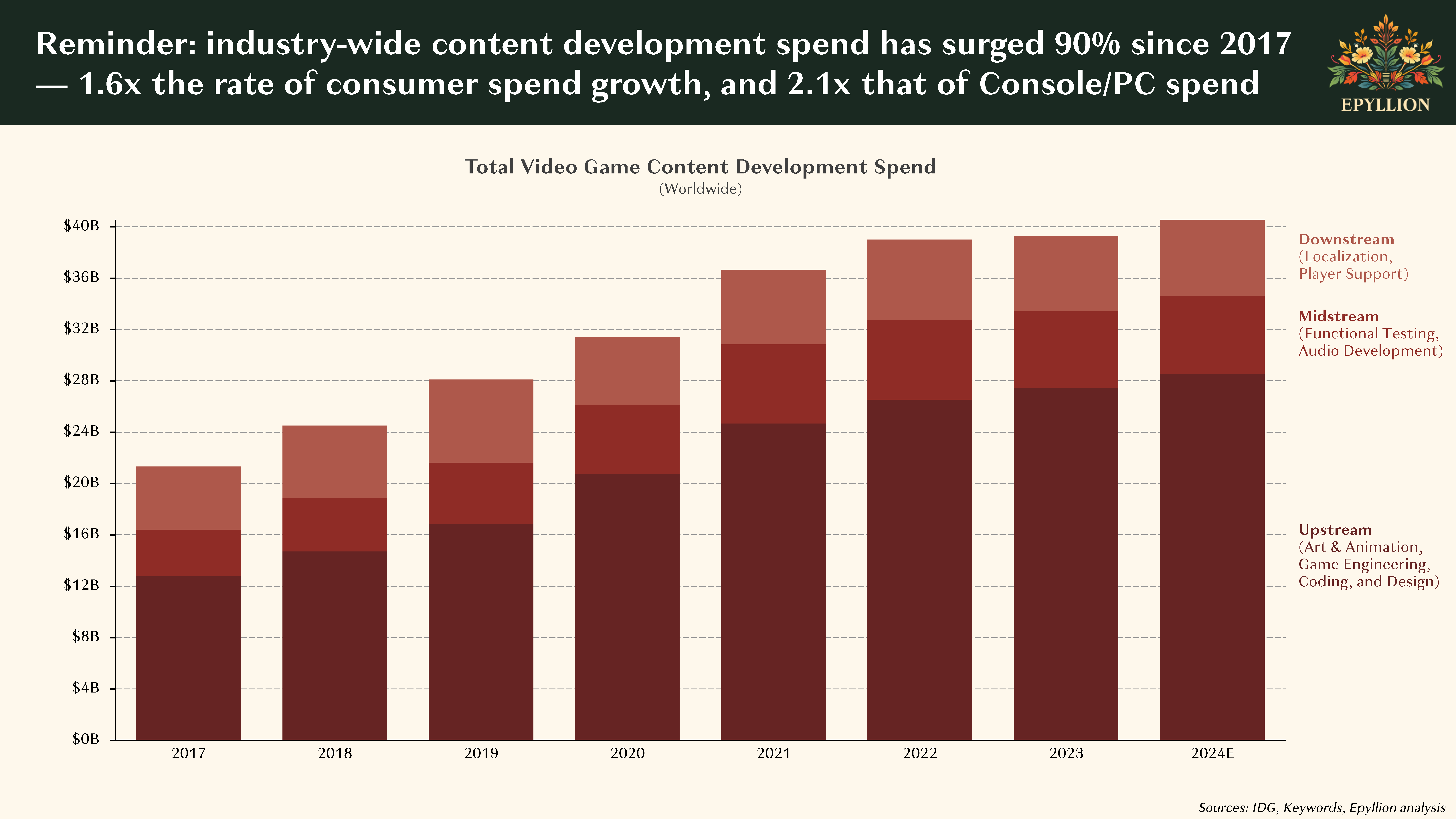

These power tools multiply human creativity, speed up production, and open the field to smaller studios. They could not have arrived at a better time. Industry-wide development costs have nearly doubled since 2017, growing far faster than consumer spending, with most of that growth going into art and animation.

The second layer is more transformative: tools that act autonomously, doing things humans can’t or wouldn’t. They make their own decisions and often surprise us. Less understood and harder to control, they produce emergent behavior that can be brilliant or counterproductive.

Live ops at scale. In 2017, Nexon’s Korea team began experimenting with early AI tools to improve live game operations, the management of large virtual worlds. One system focused on bot detection in MapleStory: identifying characters that seemed human but were actually controlled by scripts. Detecting such bots is notoriously difficult but critical. AI caught them faster, with fewer false positives, and at massive scale.

Players noticed right away. With the bot farmers now gone, players could trust that every other character was a real person unless clearly a game-designed NPC. The fewer bots there were, the more alive the world felt, as real players talked, played, and had fun together.

The team then turned to matchmaking in FPS games. Skill-based matchmaking aims to pit players of roughly equal skill against each other. Basic systems rely on crude metrics like kill–death ratios, and AI can be far more effective. Within seconds, it can analyze keyboard and mouse patterns, interpret player movement and thereby determine player skill. This is closer to how humans intuitively judge ability, and it’s far more accurate.

Even more interesting is using AI to form teams rather than just match skill. Among thousands of players online, there’s an optimal combination of, say, five people who will have the most fun competing against another five. That may depend on playstyle, not just skill. Maybe I like to hang back and snipe while you charge forward. Like any sport, chemistry between players matters.

AI can now observe and adjust player dynamics across thousands of active users in real time, evaluating and making decisions at a speed and scale no human could. In Nexon’s experience, that directly translates to more enjoyable matches, higher retention, and stronger revenue.

NPCs Thinking for Themselves: Here, AI controls enemies directly, replacing scripted “if-then” logic with genuine autonomy. Embark Studios tested this in ARC Raiders, giving its death robots real intelligence instead of designer-authored behavior. The idea is deeply evocative. The game imagines a world invaded by malicious AI, and instead of fighting scripted enemies, you are battling machines that seem sentient and intent on killing you.

The result was eerie. During one playtest I ran beneath a giant spider robot—Luke Skywalker–like—to attack its weak underbelly. The first time I did it, I got in several good shots. The second time, after failing to kill me with its missiles, it simply sat down and crushed me. I laughed, horrified and impressed by the AI’s evil creativity. When I tried again, it did the same thing, only faster. It had learned that sitting on me was the most efficient tactic.

Ultimately, Embark kept the AI locomotion system but removed the part that governed combat strategy. The robots were too good at killing but not tunable enough to make the game reliably fun. Fun is a more complex fitness function than "kill." Teaching an AI not just to win but to create fun may be the next boundary of game development, one that could open entirely new forms of play.

The next frontier goes beyond making better tools or smarter systems. It changes what a game is.

While some of today's conversation reaches this level, much of it gets stuck, not unlike print and broadcast media at the dawn of the internet. The history of games and entertainment suggests this is where the real change happens. Each major wave redefines what a game can be. GPUs and CD-ROMs made true 3D worlds possible. The internet enabled the MMORPG. Mobile phones with GPS chips made Pokémon Go possible.

AI will be the next wave in that pattern. Far beyond cheaper production, it points to a deeper change in what play means. If the past is any indication, multiple multi-decabillion-dollar companies will emerge from this shift.

.gif)

One glimpse of that future came from Mitch Lasky and Blake Robbins in their Gamecraft podcast and has since launched: Whispers from the Star by Anuttacon, a studio founded by former miHoYo leadership. In the game, you are the only contact for Stella, a young astrophysicist who has crash-landed on an alien planet called Gaia. You communicate with her through voice, text, and video, and your words shape how she survives, explores, and repairs her ship. Talking to a sentient being in distress is immediately more emotionally engaging than choosing from a dialog tree. It is a small but intriguing example of how AI could redefine the medium itself.

Leveraging AI means rethinking how we use tools, structure workflows, and iterate on creative work.

Control Issues: Traditional tools are deterministic: specific conditions (IF) trigger specific actions (THEN). While game developers use randomization all the time, the randomization is designed and adjusted precisely, by the game designers.

AI tools are probabilistic. You can train and reinforce them with examples of what you want, not command them directly. That makes them frustrating for production pipelines that depend on precision. While we are waiting for controllability to improve, the challenge is to decide where control is essential and where it is better to embrace variation, as in the example above.

Early Jank: Every new medium arrives defective by the standards of the last one. Early online games like MapleStory looked crude, and early mobile titles from Jamdat or Zynga were dismissed as toys. Early EA Sports games had camera systems that didn’t work, but grappling with that failure taught designers techniques for jump cuts and camera angles that became so refined they later made their way from video games back into broadcast sports.

Each of these examples unlocked new kinds of fun. AI is the same: rough by current AAA standards, but expansive in what it makes possible. The pioneers will see the potential before the polish.

Augmentation, not Replacement. It is natural to assume AI will replace whole departments or even the creative process itself. But revolutionary technology rarely removes humans; it changes the nature of their work. Excel did not eliminate CFOs or shrink finance teams. It made them smarter. AI will do the same for game development, elevating creators and shifting their effort from low-leverage tasks to high-leverage outcomes.

Instead of painting every tree by hand in Photoshop, artists can paint entire environments with procedural tools that already understand the biome more deeply than any artist can. The software handles what looks natural, freeing designers to focus on what makes the world fun to play in. The work is not gone; it simply moves up a level.

Every medium shift begins as a category error. Early film was “photographed plays.” Early television was “radio with pictures,” often with radio hosts sitting at desks with their sound props in front of cameras. The early internet was “newspapers on screens.”

Medieval monks who spent their lives copying books by hand thought they were in the business of writing manuscripts, but they were in the business of replicating ideas. The printing press did that work more accurately and at a scale the monks could not imagine. Turn-of-the-century horse-carriage makers did not see that they were actually in the transportation business, and were bewildered by how quickly the automobile rendered their old models obsolete.

Today, most forecasts about AI frame it as a cost-saving tool. Would we benefit from better mental models?

Better mental models for AI requires shedding the industry’s unhealthy fixation on Hollywood: its metaphors, job titles, production structures, and “greenlights.” A healthier mental model is software. Indie developers, board game creators, and the best large studios already think this way.

Embark Studios rebuilt its process for The Finals and ARC Raiders around code. Instead of hand-painting massive environments, they used satellite laser-scanned terrain, brought it into modeling tools, and generated trees, weather, and rivers procedurally. It was slower at the start but faster and more flexible forever. It showed an engineering mindset serving a creative goal.

Software-first companies in other fields do this habitually. Amazon acquired Kiva Systems, a robotics company, to reduce warehouse workers’ walking distances, but the move quickly led to a complete redesign of fulfillment centers and a massive leap in productivity. A new aerospace firm, Hadrian, has taken the idea further, building fully automated “factories-as-a-service” that connect design directly to manufacture through AI.

New waves of technology often force a ground-up rethinking. Cars did not just replace horses; they gave rise to highways and suburbs. Fax and Wi-Fi enabled remote work and paperless offices. The mobile phone created photo- and video-based social networks. New tools create systems that feel alien to the ones they replace.

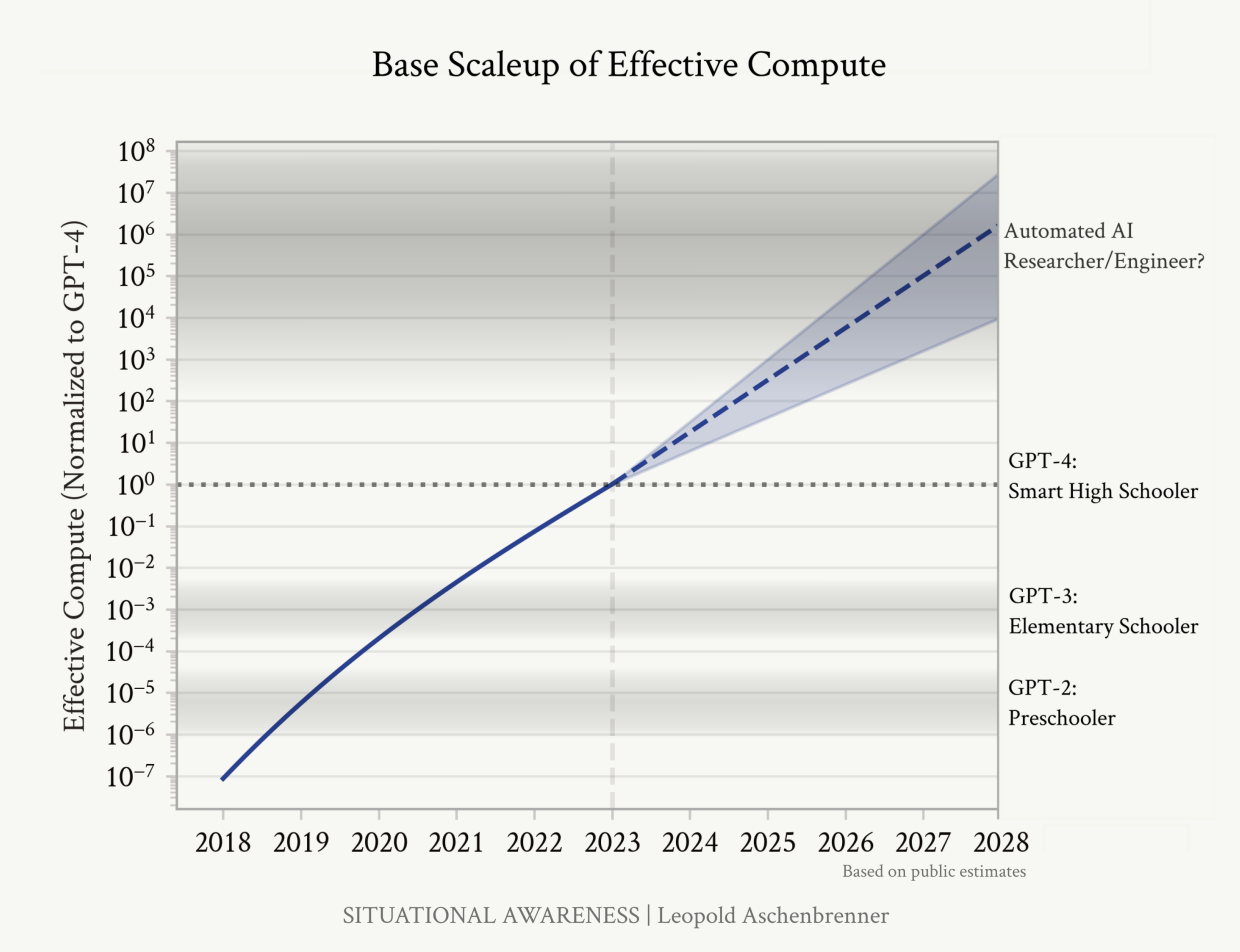

The speed of progress now exceeds anything the industry has seen. Both the infrastructure layer of chips and data centers, and the efficiency of software models, are advancing far faster than Moore’s Law, which described transistor density doubling every 18 months.

Leopold Aschenbrenner estimates that the effective compute capability of frontier AI systems has grown roughly 5–10× per year. Model scale has risen from roughly 100 million parameters in 2018 to over a trillion today.

The key point is the slope. While there are near-term concerns that the AI buildout is driving unsustainable power demand and debt loads reminiscent of the telecom boom and bust of the early 2000s, the long-term pace of progress is accelerating, not slowing. As long as that scaling trend holds, specific predictions about how new tools will shape game creation will age faster than milk.

Every medium shift favors beginners. They aren’t trapped by the old heuristics, so they move faster.

Clinging to obsolete models is one of the most common traps in business. At EA in the early 2000s, we thought we could roll over Korea and China with higher-definition graphics. Our worldview prized fidelity over online play. We were wrong. The same dynamic played out in baseball, where Billy Beane realized winning wasn’t about RBIs, but about getting on base. The same pattern has played out across technology. Google is caught between its past domination from a web of ad links and websites, and a future paradigm that is not yet defined. Intel clung to Moore’s Law even as the industry leapfrogged them with parallelism and co-processing.

The same kind of shift is coming for game development. The teams that can shrug off old mental models and reboot with beginner's mind will own the next era. As in baseball in the age of Billy Beane, once the new model becomes obvious, everyone will follow it, but the real rewards will go to those who move first.

We are now at the age of post-industrial investing in the games business. For the first time in years, games sit at the front of a massive growth wave. Many investors are starting to sense it, but few understand its mechanics.

AI will lower the cost of producing high-quality games by an order of magnitude. With the right tooling, a studio can now deliver what was once a $300 million AAA production for roughly $30 million. Embark in Sweden has already demonstrated this with basic retooling of their development stack, and they are still early. Others will follow.

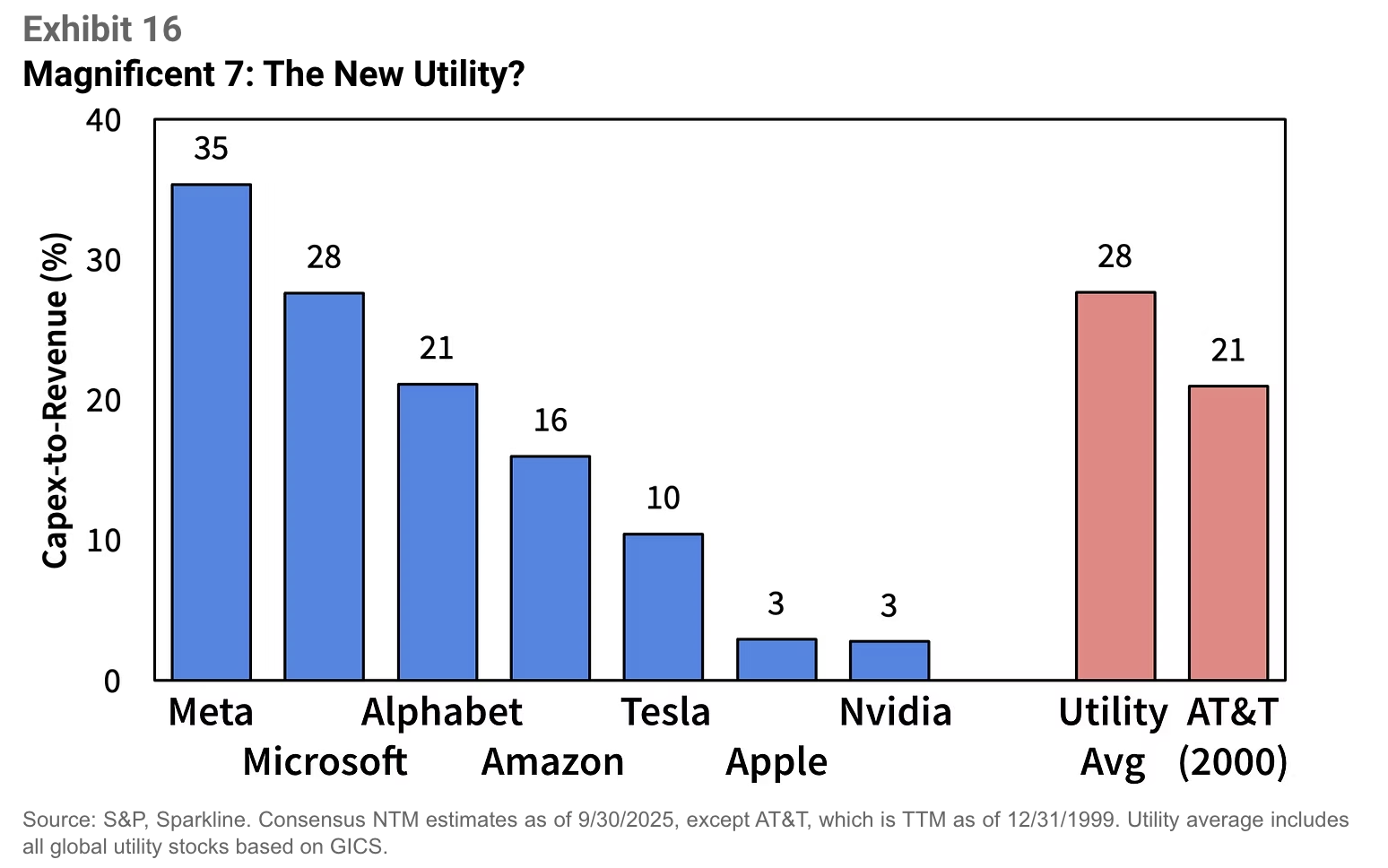

CapEx is being paid by someone else. At the dawn of the internet, telecom companies spent $26 billion laying fiber, but it was Facebook that captured the value on top. The same dynamic is unfolding with AI in games. The tool providers are funding the platform; the game creators can capture the returns. For investors, that means low input costs and extraordinary potential upside.

The real story is not cost savings but new demand. Each prior technology wave — GPU/CD-ROM, online, mobile — expanded industry revenue roughly 3x. They did so by enabling entirely new kinds of games, which in turn created new companies. The AI wave enables a similar unlock, enabling games that could not exist before and the companies that will build them. We now face a generational opportunity to create companies that can again triple the size of the market.

Where to go short: AAA incumbents whose competitive advantage came from scaling large teams to build a game. As Brian Reynolds, former lead designer at MicroProse and Firaxis, put it, “I used to design in real time. Now on AAA games, I design the game, then wait 24 months for the assets to be built so I can start designing again.” AI collapses that delay and wipes out the incumbents’ advantage. The mass production apparatus that once gave AAA publishers leverage is now an albatross.

Where to go long: teams free of legacy methodologies have a decisive advantage. They can use new tools to invent new play patterns and open new markets. Nearly every winner of a platform shift has been a new company, unbound by old assumptions. Roblox looked crazy when it first appeared, just as Audible did on the early internet and Spotify and Waze did on mobile. Each used new technology to create new user experiences. The same kind of unexpected winners will emerge in this next wave.

The entire industry chessboard is being tossed in the air. For investors, there has never been a better time to invest.

AI and related tools will restructure the creative economy. The first wave grew around internet platforms like YouTube, Twitch, and Pinterest. The second wave centered on tools like Shopify and Roblox, which allowed individuals and small teams to build and monetize experiences. The next wave, powered by AI, will go deeper, replacing much of the industrial layer of game development: the armies of artists, designers, and coordinators who translate creative direction into production assets. What was once labor-intensive OpEx becomes automated CapEx.

That shift will be painful in the short term. The industrial layer employs vast numbers of hard-working people, organized through one of the most complex managerial systems in business. It will feel very frightening to many who built careers within that structure. But the same transformation that hollows out the industrial layer dramatically expands the creative one. It moves leverage upstream, from coordination to creation. The hopeful path for today’s developers is to move in that direction, to master the new tools, experiment, and focus on design, systems, and creativity rather than production management.

This change also undercuts the traditional power of large publishers. Their advantage was scaled content production, the ability to substantiate a game by financing and managing thousands of people. As production costs soared, fewer companies could afford to compete, and that scarcity reinforced their dominance. In the framework of unbundling, publishers controlled the final bottleneck: substantiation. AI removes that bottleneck, and with it the last source of oligopoly rents and power.

So while it may look like an apocalypse for developers, it is really a reckoning for the industrial structure that has dominated games for two decades. For creative people, it is a rebirth. The analogy to movie and television studios in the age of YouTube and TikTok feels apt. We could soon have more creators, not fewer, people actually making things instead of managing others.

Nothing suggests that AI will replace creators who imagine new worlds, design systems, and collaborate with others to create fun. It will replace routine production, not creativity. The best developers will treat these tools the way great artists once treated new paints or instruments: as ways to explore ideas faster and farther than before. The next Sid Meiers, Shigeru Miyamotos, Will Wrights, or Jake Songs will be the ones who master these tools to invent new forms of play. AI will not replace human creativity but expand it, enabling the smallest teams to accomplish what once required the largest.

“In times of change, learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists.”

- Eric Hoffer

AI is not merely a tool. It is a change in the medium itself.

It is a deus ex machina, something that appears unexpectedly and rewrites the script. It delivers enormous improvements in experience, is largely being funded by others, and removes the final structural advantage of the incumbents.

Every real medium shift is alien at first and therefore frightening. We focus on the visible disruptions of job losses, cost cuts, and the collapse of familiar systems. What is harder to see, and far more important, is the opportunity it creates.

Each previous wave of new technology in games multiplied the number of creators: from thousands in the PC age, to hundreds of thousands in the console and online era, to millions in the mobile wave, to tens of millions in the age of UGC platforms like Roblox. AI will multiply that again, by empowering new developers and vastly expanding the creator economy in game development.

In Derek Zoolander, Videogame Exec, I wrote that we often mistake hype cycles for meaningful technology waves. This time it is not a fad. It is an evolutionary leap. Every medium shift opens a doorway to a larger world. Progress belongs to those able to see it with a beginner’s mind.

Note: Thanks to Bing Gordon, who pushed me to think more deeply about this topic and shared many sharp insights. Any mistakes are my own.